Expensive ship built by failed company indicates structural flaws in niche industry.

This week, the Dutch maritime giant Boskalis unveiled its newest ship, the Windpiper. Her intended use - supporting the construction of offshore wind farms - is interesting, but I’d like to take a look at her past. We’ll loop back at the end.

The Windpiper won’t be a new ship; she’s a conversion of the Nautilus Era, a ship which was (mostly) built back in 2018 for seafloor mining. The company who commissioned her, Nautilus Minerals, was planning to extract copper and gold ‘nodules’ sitting on the ocean floor in Papua New Guinea. The ship was designed specifically for operating three vehicles which would drive around the seabed and pipe the minerals back to the surface. Imagine a team of Kreepy Kraulys all hooked up to a big ship, but they produce copper instead of leaves. The project was scheduled to begin production in 2019.

The fact that the ship is now doing something else, and I’ve been using the past tense, will indicate that this did not go to plan. The full story of Nautilus’ collapse has been covered elsewhere and is interesting, particularly around the environmental and governance angles. However, I’d like to focus on what the story might tell us about the difficulties funding seafloor mining, both then and now.

Skipping to the end - a series of calamities led to Nautilus declaring bankruptcy late in 2019. While the project itself somewhat mysteriously limps along, the Nautilus Era ship was up for sale for some time, before recently finding her new home. I argue that the story of the Era can tell us a lot about a problem which will be common to most seafloor mining projects and sits completely outside (very valid) environmental concerns. This is a finance problem.

In the normal order of things, a mine developer finds something worth digging up, then makes a slide deck and goes looking for someone to finance the mine. Financiers will lend the construction costs of the mine and a bit of walking-around money, in exchange for interest and taking security over many things, including the exclusive mining licences, all of the equipment required to do the mining, the shares in the relevant company, contractual rights, and/or the cashflows from the mine itself.

Specifics vary, but a developer can usually expect to keep ownership of most of the things to run the mine, both tangible and intangible. Those things will be pledged to the bank to be seized if the developer defaults on the loan - in theory at least. Importantly, mobile plant like trucks are always a bit of a headache for banks in this context because they can drive away - it’s important to know where something is if you would like to seize it. Lucky for lenders, security can be enforced fairly easily against holes in the ground and fixed plant like mills, because they tend to stay put.

Not so for ships. Mortgages can and are taken over ships by financiers, and there is a complex and arcane set of rules about how they can be enforced (including the delightful concept of a ship arrest). But ships can also sail away to international waters, or less salubrious jurisdictions where courts might not enforce a foreign mortgage. This can make banks nervous that their loan collateral will literally sail away - adding to all of the other issues one may have with ship builds (cost, volatility, environmental liability, sinking). Nautilus would have had at least four major problems standing between it and getting project finance. The Era was to be very expensive; it was built for a specific purpose so couldn’t be easily repurposed and sold if the project failed; ships are risky at the best of times; and there was uncertainty around the concept of seafloor mining as a whole. It must have made it extremely difficult for Nautilus to make the case to get a bank loan to build the ship - one of the most important steps in the project’s development.

As we now know, it couldn’t, and didn’t. Instead, an arrangement was struck where a charismatically-named corporation named ‘Marine Assets Corporation’ would own and operate the marine asset, being the ship. Nautilus, as the only natural customer, would charter it back for an oddly precise $199,910 USD per day, in 2014 money. Government grants, shareholder loans and bridging loans were to cover the rest. By entering into this arrangement, Nautilus was putting the vast majority of its eggs in MAC’s basket. In a seafloor mining operation, the production ship acts as haulpac, conveyors, processing plant, base camp, and, critically, the ship acts as the mine pit itself.

A terrestrial mine can’t access overburdened ore without digging holes, and an oceanic mine can’t access seafloor minerals without a ship. Due to its inability to get finance, Nautilus was forced into a position where it would not own its critical infrastructure, only pay for its usage. They had agreed to rent a house that wasn’t built yet, and as it turns out, the ‘landlord’ decided to stop building halfway through. When MAC decided to stop paying the shipyard before the ship was finished, it became the yard’s property. Nautilus no longer had the specialised ship that it needed to access the minerals it (may have) been entitled to, and so it found itself with very little to fall back on.

Nautilus could only watch as the Era was sold on to ‘Ocean Energy Ventures’ for oil and gas work (which apparently also didn’t work out). Without another ship, there was no viable means of progressing the project. In the onshore mining world, this would be like watching your mine pit march itself down the road and become an oil well. You might still have the rights over your patch of ground, but the rocks you want are buried again, and now you can’t afford a shovel.

This seems to be the critical difference between Nautilus’ arrangement and the established concept of contract mining, where someone else mines your deposit for you. If a contract mining arrangement falls over, you probably still get to keep your pit so it’s easier to access the ore. In seafloor mining, it’s essentially back to square one.

The Nautilus project may have been doomed from the start for other reasons, but it certainly wasn’t helped by a lack of finance forcing the company into a position where a third party held all the cards and could sink the project. My question: is this project-specific, or will it be true of all seafloor mining projects?

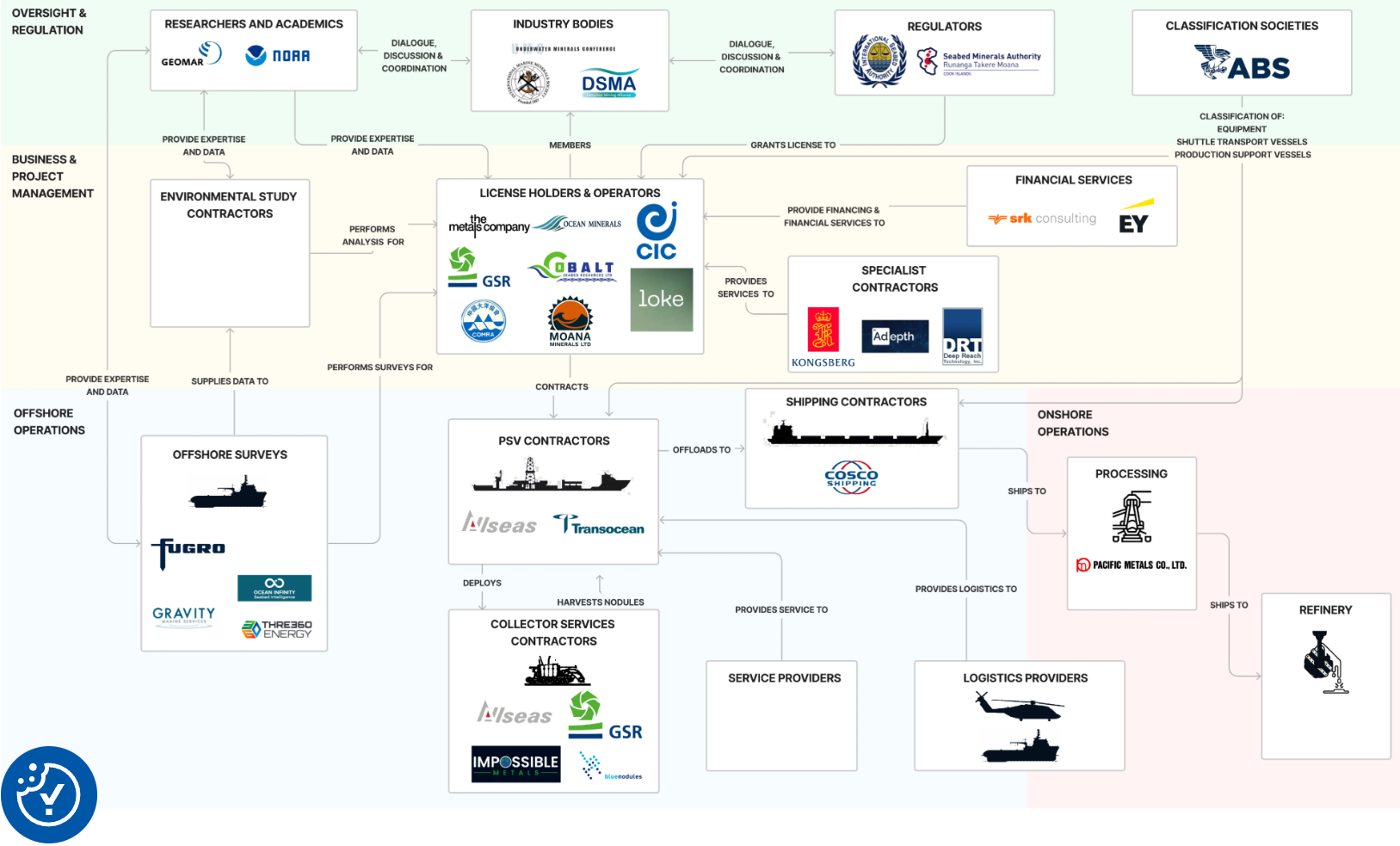

Seafloor mining hasn’t exactly taken off since 2018, but companies, led by The Metals Company, are forging on. The same commercial pressures faced by Nautilus still largely apply, so it’s interesting to see how they are being approached. Project financing is still presumably still very hard to come by. TMC had the benefit of zero interest rates, the SPAC money-bucket and a high-profile listing, but it still requires development capital. Among other things, TMC is financed by an unsecured director loan and, interestingly, an as-yet undrawn loan facility from shipping giant Allseas. That facility is part of a broader partnership between Allseas and TMC.

In this partnership, Allseas will own and operate the ship and all of the mining equipment on board. It seems to hinge on a fee structure where TMC pays Allseas for each tonne of metal recovered (~EUR 150/tonne is the going price of a nodule, if you’re curious). This amount is not finalised, with the final price to be agreed at a rate ‘sufficient to cover Allsea’s operating expense […] and a fee linked to the value of the contained minerals’.

Clearly the exact nature of this agreement will be critical for the viability of the project. A cynic might suggest that it is a somewhat risky move to enter into a contract with a critical service provider, who is much larger than you and effectively controls your fate, in which that service provider gets to decide their own profit margins. While I am sure this co-development partnership is strong, based on mutual trust and the potential for significant profit, it is less than ideal for a project developer to be so beholden to a third party. In good news, this arrangement removes much of the need for project financing, as most of the capital expenditure is being made by a third party. In bad news, the project developer might be left with little control over their cashflow and few assets to secure further borrowing to change the situation.

TMC are experienced and well-resourced, so we might assume this is the best approach available. There is another option where the developer has traded a non-controlling share of the company to a shipowner in exchange for the use of a ship. There may be more creative solutions (offtake, royalty, factoring?). However, I think that in most situations, the project owner will be deeply dependent on, and subject to the whims of, a much larger shipowner.

In my mind, the situation can be summarised thus:

Seafloor mining project developers need specialised, expensive ships to extract value.

Unless the developer already owns such a vessel, it will need to procure one.

Banks will be unwilling to finance the construction of such a vessel as it is expensive, specialised mobile plant operating in an uncertain industry, and the developer has few other assets to take security on. Alternative funding might be possible, but represents huge expenditure.

Therefore, the only viable path may be for the vessel to be owned and/or operated by a third party, which charges for the service in one way or another.

The vessel is absolutely critical for the profitable operation of the mine. There are few, if any, viable replacements. The shipowner therefore has effective control over the project.

In a best-case scenario, the shipowner takes a healthy profit to reflect the fact that they are taking a huge risk - which might work until market conditions change, or one of the other myriad problems involved in running a mine rears its head.

In a moderate scenario, the shipowner charges as much as required to keep the project developer beholden as a captive customer making just enough money to keep the lights on, but unable to raise additional funding to change the situation. These limited returns would hardly seem to be worth the significant risk for equity investors.

In a worst-case scenario, the vessel leaves for a more profitable sector, or sinks, taking the project with it.

As I see it, the only thing which could potentially change the picture is where the project developer also owns the means of production, in this case, the mining ship. One could imagine a situation where a shipowner decides to chase the huge potential of seafloor mining by procuring and using its own ship. There are many reasons why they may choose to go down this route, or not - none of the companies involved are stupid, they have resources that I don’t, maybe there is a financially viable way to conduct seafloor mining, even setting aside the ESG concerns.

But remember that Boskalis just bought a seafloor mining ship, one of the very few in the world - and they’re rebuilding it to work on wind farms.