I’m not just delving into the inherent contradiction between the use of AI and the obligation to act with care and diligence; I’m suggesting that the technology should not be used at all!

Let’s say I was to offer a new service. You’re a company director, and you have board meetings coming up. You have been given a board pack to review before the meeting. It is a mighty beast; Outlook attachment limits cower before it. Lots of words and numbers, who knows what’s going on in there.

Never fear. For a very reasonable fee, I will take the board pack from you, select five pages at random, and use those five pages to create a beautiful, concise 200 word summary. The other pages have been thrown away but that’s fine because you didn’t want to read the unlucky pages anyway. I’ll include a chart. I shan’t answer any questions on what I did and why, but it will look good. You are now ready for your meeting.

Quality delivered.

This is, of course, a silly thing to do, and no responsible director should hire me to do so (though if you’re paying, I will reserve my judgement). But replace me with one of the many AI platforms currently available, and now we’re ‘leveraging technology for efficient board operations’. We are told that AI technology can ‘drive superior governance outcomes’, though we are cautioned that we need to consider how we might ‘use AI to increase efficiency while ensuring there are appropriate governance controls in place’. The message seems to be ‘you can do this, it’s awesome - oh but of course, be careful - wink’.

I have no doubt there are directors across the country who are feeding their board packs to AI and turning them into summaries prior to meetings. They may also be generating meeting agendas or minutes using AI. They might suspect it is a bit naughty, but the corporate governance people seem at least generally permissive. It’s very hard not to play with a shiny new toy - especially when that toy makes your life easier. When the board meeting is at 9 tomorrow and the dinner reservation’s at 6… one can understand the temptation. One might even justify it to oneself as being a forward-thinking, tech-savvy industry leader, driving efficiencies.

I’m definitely fighting the tide here, but I don’t think there is any situation where an Australian company director should use any form of AI in the carrying out of their duties, especially in reviewing board material. It’s not a grey area, the two are fundamentally incompatible. We don’t have to play with the new toy.

To clarify: I am not talking about individual workers or consultants using AI to assist in doing their jobs. I used it to help me write this. AI streamlines a lot of ‘email job’ type operations, which is a (qualified) Good Thing. I’m talking specifically about the use of AI by directors while they are doing their directoring, where they are subject to fiduciary duties to the company.

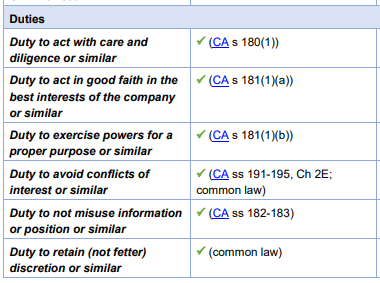

Key among these are the duties to act with care and diligence and not fetter one’s discretion. Directors need to actually pay attention, give consideration, and exercise their judgement. While this obligation doesn’t end at ‘read the board pack’, it definitely starts there. Matters can of course be delegated, but that’s an active decision which has been made in respect of a particular area. A director can’t wholesale delegate themselves out of the responsibility to pay attention.

My ‘review case law on director’s duties and write a summary’ days are mercifully behind me, so please take these ticky boxes from a quite good law firm’s report to the Australian Institute of Company Directors as evidence that the duties exist. You may also wish to refer to these first year lecture notes I found.

Put simply, I think that the moment a director asks an AI - any AI - for a summary of board papers, they might be failing to uphold their duties. I don’t think it’s something which can be mitigated. A director who relies on black-box summaries is not acting with care and diligence, and are fettering their discretion because a service provided by a third party is setting the decision-making framework.

I am no AI scientist, and I presume you are not, either. We don’t need to be to understand the concept of how large language models work. We can use a platform like Claude, or Google Notebook LM, or (my preferred) Perplexity, to summarise long documents into short ones. We upload the file, and something happens. The platform does a really good job of guessing the next word based on context, and we end up with some more or less convincing text (even though it will probably use the word ‘delve’ and insist on unnecessary counterpoints). The product is good, but you don’t see what parts of the source documents have been preferenced, ignored, or misinterpreted. Outliers may have been disregarded as the algorithm tries to work out what the most likely next word is. The AI won’t tell you what parts it decided to disregard, or why. For a director, those outliers are probably the important bit.

The important thing buried on page 38 and missed in the summary is an ‘unknown unknown’, but the ‘known unknown’ is that you haven’t read everything.

Drawing bold conclusions from incomplete data using opaque decision-making processes has proven to be a risky strategy.

The point isn’t so much that the tool produces bad results. I’m arguing that the director has not read all of the information presented to them and so cannot, in any situation, have fully considered it. It’s a pretty simple argument - embarrassingly so - but it is resilient.

What if the AI gets it right? Doesn’t matter, the director didn’t read it. Furthermore, what does the ‘right’ summary mean? I don’t think it’s too postmodernist to say that any summary inherently involves selection and interpretation. A director is paid for their ability to make those selections and interpretations, not pass them off.

What if you keep a record that you’ve used AI to summarise the papers? Doesn’t matter, ‘I put it into a magic black box’ isn’t the same as a delegation, not least because there’s nobody else to blame. And who is going to formally record that they were delinquent in their duties? I’d argue that given the recent trend away from taking and keeping detailed notes to limit liability, directors are better off just doing it without saying anything.

Yeah but directors don’t read most of the stuff in board packs anyway, so this is better than nothing. The unsecured creditors will be thrilled to learn the board switched from unintentionally failing to pay attention, to intentionally not paying attention.

Directors today are presented with far more information than they can reasonably read and process, particularly when they sit on multiple boards. Doesn’t matter, the director didn’t read it. If there are too many inputs into a system, the solution isn’t to stop processing altogether. One may consider demanding shorter board packs from management, or perhaps even sitting on fewer boards. The director in the piece linked above is complaining about having to read 1,600 pages per month in board papers, which is indeed quite a bit, but definitely doable and no doubt well remunerated. Those pages, however, are spread across four different boards. 400 pages in a month is within the striking range of most book clubs; The Hunger Games is 384 pages long. The later Harry Potter books where it all gets a bit spooky are considerably longer.

Some documents can be accurately summarised using AI.

What if the director reads everything then gets the AI to create a summary as an aide-memoire? An interesting outlier, because here the director has read everything. Aside from the obvious ‘well then you didn’t need the AI’, this seems to be getting into Thinking Fast and Slow territory. I think the risk here is that a nuanced view which comes from careful study of the material is at risk of being bludgeoned into submission by easy conclusions from a summary prepared for easy digestion. It’s the ‘brash idiot vs quiet thinker’ cognitive closure thing.

My thesis is that relying on third party summaries of the information presented to you as a director is irreconcilable with the fiduciary duty to do a proper job. It doesn’t matter if it’s an AI doing it, or me. While I recognise that almost everything is a summary of something else, we need to draw a line between ‘you really need to have read this bit’ and ‘this is additional information for the real heads only’. Board papers is the reasonable place to put that line. I don’t think it is unreasonable to expect a human director to use their real human brain to read the documents which are specifically handed to them. That human brain can also be used to set the agenda for meetings and make decisions based on the content of those documents. In that context I am at somewhat of a loss as to why some groups, including the Australian Institute of Company Directors, seem to take it as a given that AI will be used in the context of board operations, this is a good thing, and all we can do is wave our hands vaguely at mitigation. The possibility that it is a wholesale bad idea does not come up.

The AICD’s ‘Directors’ Guide to AI Governance’ spends most of its time focusing on the use of AI within organisations, and how directors can manage the risks and opportunities thereof. There is a brief consideration of directors duties, stating that:

Directors have a fiduciary duty to act in the best interests of the company. When making decisions and providing oversight regarding their organisation's development and use of AI systems, directors are required to act: with due care and diligence; and in good faith, and for a proper purpose. Focus is growing on the duty of care and diligence in the context of governance failures in meeting cyber security and privacy obligations, which are both relevant considerations in the use of AI systems.

Far be it from me to question the wisdom of the AICD (from whom I have learned a lot) but this feels like a narrow interpretation which assumes that development and use of AI systems is unquestionably going to be happening. The words ‘fetter’ and ‘discretion’ do not appear. Using AI summaries isn’t just a question of cyber security and privacy as is implied here, it’s a fundamental question of whether or not a director is actually doing their job or whether they are delegating operations and governance to a third party. Not everything can be mitigated, and the correct answer is not always ‘OK but be careful’.

This article, released by the AICD after the above report, takes it as a given that AI ‘will have a significant impact on boardroom operations and governance’. One suggested use case is putting all board data in a database and getting the AI to quite literally set the agenda. Another is that everyone’s anonymised board data is thrown together so decision makers can mindlessly copy be guided by their peers in similar situations. We touch on the risks associated with AI minute-taking, but that same sentence also makes sure to first mention how it’s incredibly productive. This remarkably bullish, and in my opinion quite risky, viewpoint can perhaps be explained by the fact that the article was brought to you by a company which makes AI software.

I dispute the assertion that ‘directors cannot ignore AI or make only minor adjustments, but should instead embrace the AI opportunity, while carefully assessing the risks involved.’ You don’t have to use the new toy for everything, particularly if you think it is fundamentally incompatible with your legal duties. Many effective boards operate just fine using the technology of 1999. This has echoes of when companies were hiring Chief Blockchain Officers and directors were being told that they ‘need to be aware’ of DAOs. As much as I’m an advocate for new technology, the fact is that most directors did not, in fact, need to be aware of DAOs. You don’t have to do do the new thing just because it’s there.

You don’t have to drink from the puddle.

I know I’m against the tide here and nobody likes a scold. So, if you’re still with me, in the absence of reiterating an somewhat abstract point about common law duties, I encourage you to test the powers of AI summaries. Ask a search-enabled AI of your choosing about a topic upon which you are an expert. Really grill it on your niche subject area. I don’t mean the 2018 AFL Grand Final, I mean something really niche, a tiny area you are a world expert in. See if it gets all the details right. Even if everything that’s said is accurate, is it complete? Would you trust that summary to replace your understanding, 100 times out of 100? Would you bet your reputation on it? AI errors aren’t as funny as they used to be, but they haven’t gone away.

This excellent blog post talks about the relative value of unsupervised AI (which, to be clear, is what we’re talking about when we’re summarising documents). I highly recommend you read it if you have made it this far. In short: unsupervised AI is really good in low stakes environments where mistakes can be made - because it will make mistakes. That’s fine if the AI is being used to recommend your next Facebook ad (it seems convinced I am interested in buying Indian onions by the tonne). It’s not fine if the AI is doing your thinking for you and deciding what parts of your board papers are important. People’s careers rest on those decisions. You’re a world expert on your own business, act like it.